A Little World

When the Kingdom of Italy signed an armistice with the Allies in 1943, Germany still controlled much of the country, and thousands of Italian soldiers who refused to fight for the Axis were shipped to internment camps outside Italy. One soldier, a 35-year-old journalist named Giovannino Guareschi, was sent to a camp in Poland. On the way, he encountered a Catholic priest named Don Camillo Valota, who had been arrested for aiding Jewish refugees. Valota was on his way to Dachau.

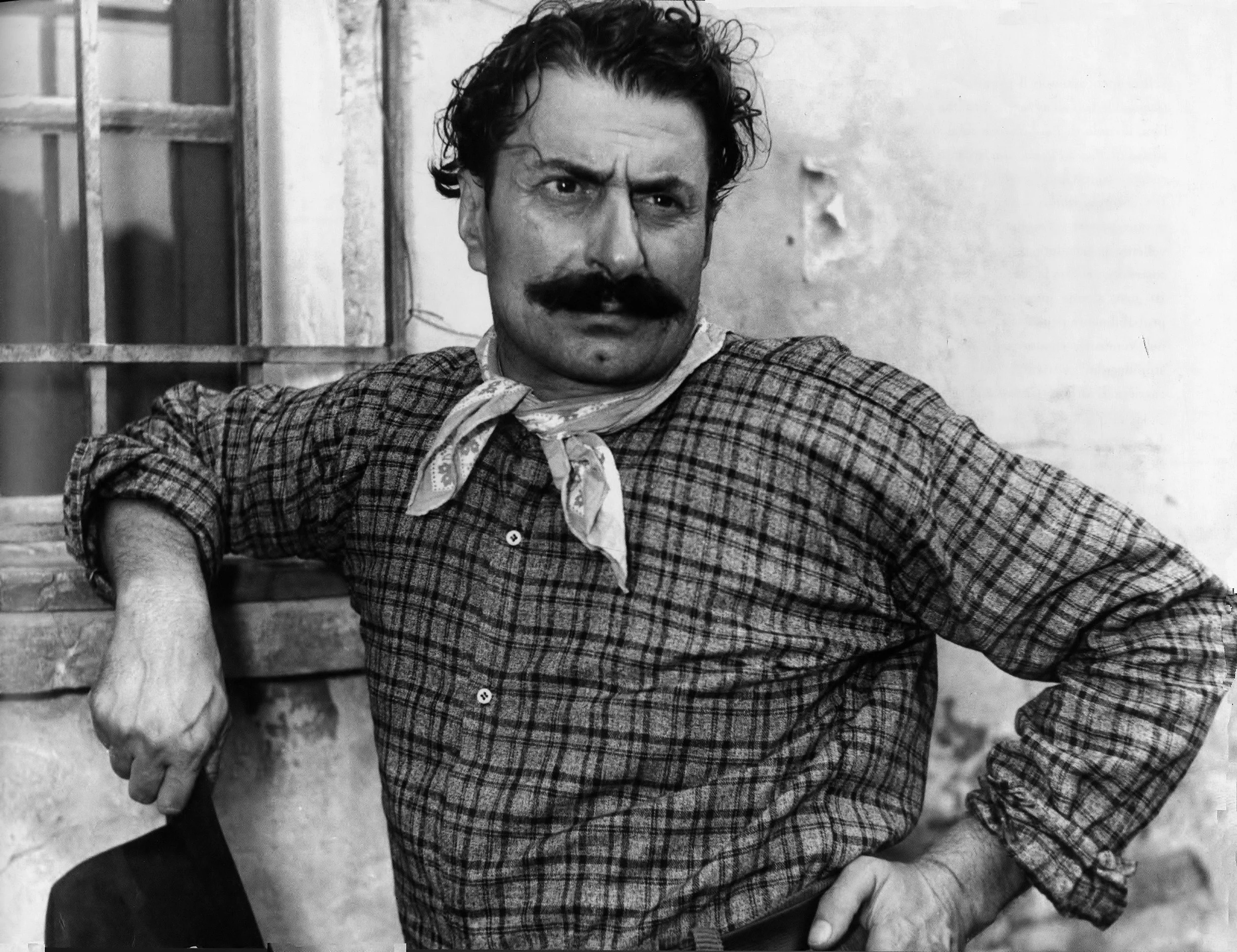

Giovannino Guareschi, author of the Don Camillo stories

Guareschi survived. The war ended. Back in Italy, he began to write stories about a small town on the River Po, and the town’s hot-headed, stubborn, fearless priest, who has an equally obstinate arch-enemy, the town’s Communist mayor. Guareschi named the mayor Peppone, and called the priest Don Camillo.

The stories are splendid evocations of post-war rural Italy, and a country struggling to find its place in a changed world. But they are also funny, poetic and wise pictures of imperfect people who manage to be human despite religion and politics. In one memorable scene, Peppone, a little unclear on the Communist concept, infuriates Don Camillo by bringing his new-born son to be baptized “Lenin”. Don Camillo is instructed in tolerance by frequent conversations with Jesus, in the form of a talking crucifix.

Gino Cervi and Fernandel, and the infant “Lenin” in “The Little World of Don Camillo” (1952)

The stories were best-sellers when published in book form. In 1952, the French film director Julien Duvivier made the first of a series of films about the little town on the Po. It was a joint French and Italian production called “The Little World of Don Camillo,” with the great French comedian Fernandel as Don Camillo, and the superb Italian actor Gino Cervi as Peppone. The five films in the series are among the most-loved of Italian movies.

Fernandel as Don Camillo and Gino Cervie as Peppone in “The Return of Don Camillo” (1953)

Duvivier chose the atmospheric little town of Brescello, on the banks of the River Po, as the setting for the films. It was an inspired choice. If you visit Brescello, it’s like going back to Don Camillo’s little world. The talkative crucifix is still in the church, Santa Maria Nascente. Don Camillo’s statue blesses the main piazza. Peppone doffs his cap across the way. Mementos of the films are in the Peppone & Don Camillo Museum, a former Benedictine monastery. Giovannino Guareschi Park has a bust of the author.

Brescello’s railway station, by Moliva, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Far away, here in the southwest United States, we recently had Italian visitors, four women travelling together, enjoying the Grand Canyon and other local sights. They insisted on making spaghetti carbonara for us and some other friends, so we all gathered in our kitchen. The possible Greek exit from the Eurozone was in the news then, and we talked about the tensions in Europe between the north and south. We talked about the effects of austerity on people’s lives, and its similarity to the post-war suffering people endured in Europe, which somehow led to a discussion of social realism in great Italian cinema. Then someone mentioned Don Camillo. “Ah … Don Camillo,” a second voice murmured. “… and Peppone!” a third added happily. I looked around the room. Everyone was smiling.

© Text © 2015 by Joe Gartman; Photographs © 2015 by Patricia Gartman. First published in Italia! Magazine, November 2015