Piranesi and the Shadows of Paestum

One bright December morning last year in Salerno, we awoke and ventured down the vertiginous stairs from our rented apartment into Piazza Portanova, where we’d spent the previous evening photographing the riotous holiday festivities in the packed square. The giant LED Christmas tree was switched off. Workers from the bars wearily set out tables and chairs amid the litter. We decided to forego breakfast and take the train south along the Tyrrhenian coast, to Paestum, for a change of scene and a visit to the past.

Temple of Athena, Paestum

On the train, I tried to recall the few facts I knew about Paestum. I’d read about it, of course. I remembered that it was a Greek colony back in the 6th century BC, one of the many Greek settlements collectively called “Magna Graecia” by the Romans, that were scattered, like clinging burrs carried by an east wind, onto the coasts of Sicily and southern Italy. Some took root and still survive – Naples, Taranto, Reggio Calabria, Messina, Agrigento, and Syracuse. But most are gone and forgotten.

At first, I found it difficult to bring the history to mind, because when I closed my eyes to concentrate, images, like engravings in old books, filled my mind: nightmarish pictures of great temples crumbling away, their mighty Doric columns and fallen capitals festooned with weeds, shrubs, and even small trees growing from the fractured stone, with barely distinguishable figures lurking among the ruins – all shadowed darkly under a lowering sky. At last, staring at the sunny landscape rushing past, I managed to get back to the facts of Paestum.

Interior of the Temple of Hera, Paestum, by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, 1778

Poseidonia, it was called, and it was founded by settlers from Sybaris, a wealthy and pleasure-loving Greek colony on the Gulf of Taranto. People from Sybaris were called Sybarites. Today the word describes self-indulgent or decadent people. But the settlers were of sterner stuff, and built a handsome town near the sea and the river Silarus, with walls, gates, a splendid agora and, of course, temples. Around 400 BC, however, Poseidonia was conquered by the neighbouring Lucanians, who ruled until the Romans kicked them out in 273 BC, and set about replacing the Greek town with a Roman city with a Roman name – Paestum. They kept the temples, though.

Interior of the Temple of Hera in 2024 - looks a bit familiar!

For eleven centuries Paestum endured. Rome’s empire came and went. But silt eventually began to gather in the Silarus River’s mouth; and in time, the once fruitful plain became a malarial swamp. The population dwindled, until, in 871 AD, when marauding Arabs arrived to sack the city, most people had already left. The Arabs decided not to settle, though it seems they left a few water-buffalo behind, who found the soggy terrain to their liking. (Their descendants now are farmed locally and produce a highly prized Mozzarella di Bufala.) Paestum was forgotten for more than 900 years, except by a few herdsmen, hunters, and vagrants who occasionally braved the dreaded swamp.

Temple of Hera at sunset

We stepped off the train at Paestum’s small station, crossed the road, and entered the town beneath an arched, 1st century Roman gate. I thought of how 18th century Grand Tourists had flocked to the temples, their interest in antiquity piqued by the discovery of Pompeii and Herculaneum. Well known writers, like Henry Swinburne and Goethe, visited and wrote about Paestum. A collection of engravings by Giovanni Battista Piranesi – the source of the dark images I’d remembered on the train – helped cement Paestum’s romantic appeal.

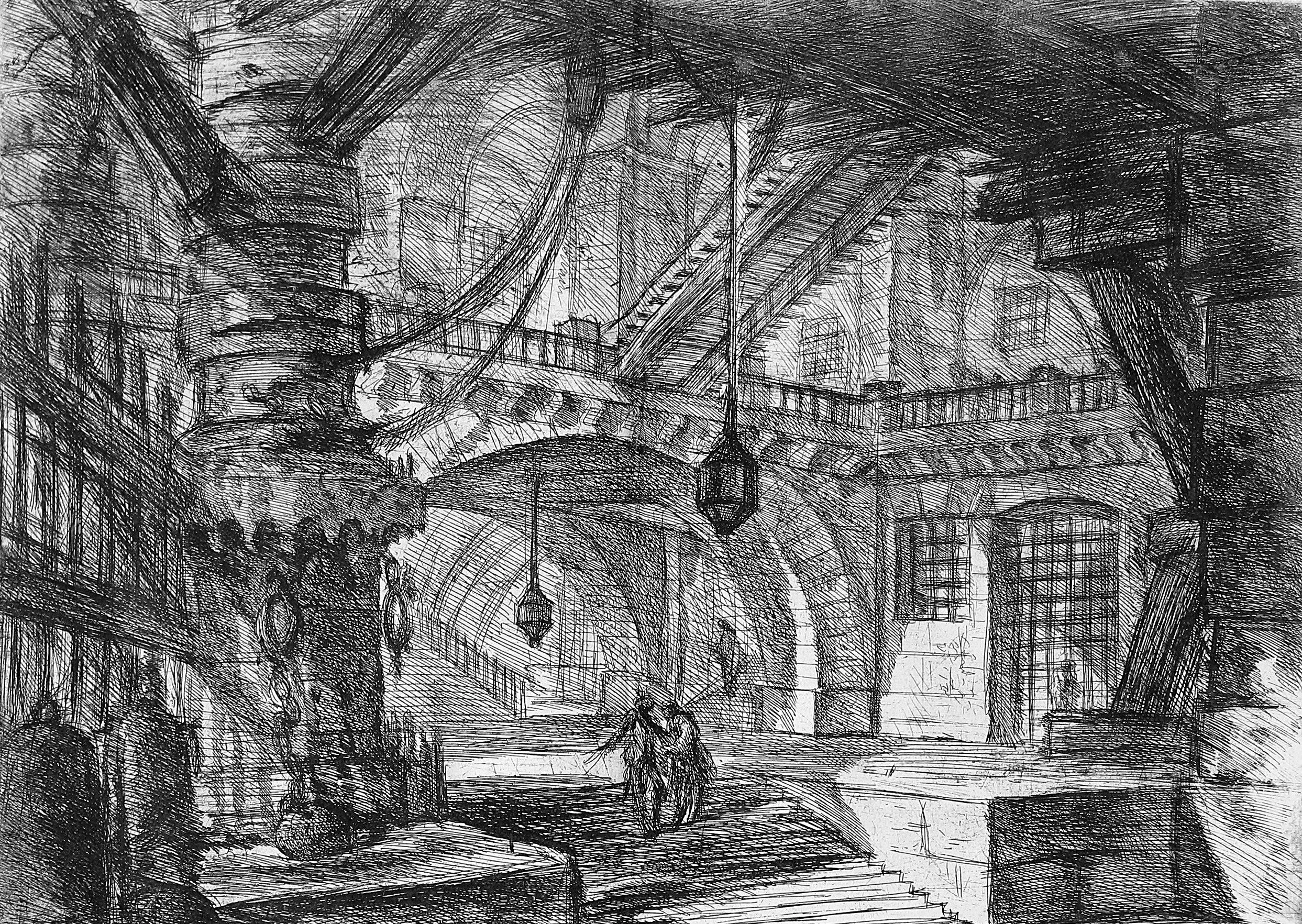

Piranesi is remembered by art historians today for his scenes of both Paestum and Rome, and a disturbing set of prints depicting tiny human beings in enormous “Imaginary Prisons” – Carceri d'invenzione – huge, dark, sinister classical interiors with galleries, mysterious machines, and staircases that disappear in distant shadows. His brooding pictures of Paestum, though not so nightmarish as the prison prints, were still moody enough to capture the imagination of the Romantics - artists, poets, and especially architects – throughout Europe, and helped spread the “Greek Revival” architectural style far beyond Magna Graecia and Greece itself.

Giovanni Battista Piranesi - Le Carceri d'Invenzione - The Pier with Chains, c. 1750

Today there’s no swamp, and it seems the mosquitos are gone. The temples are there, in stunning magnificence. In the sunlight, the best preserved of them, traditionally called the Temple of Neptune, still shoulders both pediments upon its 36 mighty exterior columns. Visitors can enter the temple on worn stone steps and wander around the inner columns of the cella (where the deity image would have been). This is something that the people of Poseidonia could not do – the temple was the home of a god, who could be served indoors only by the priests.

Temple of Neptune (newly renamedTemple of Hera II) c. 450 BC

Nearby, across a hundred feet of manicured lawn, the Temple of Hera was once thought to be a municipal building, and was originally called “the Basilica.” It’s older and not as complete as the so-called Neptune Temple. (Both temples, it seems, have recently been renamed for Hera). A kilometre or so north, past the remains of the Roman town, is the smallest temple, named for Athena, sitting prettily on a flower-dotted knoll.

At times, as we explored the great buildings, a glimpsed detail would catch my eye, and I would think, almost as if I’d been there before – that gap in the cornice above the second triglyph from the right – shouldn’t there be a sapling there? It’s Piranesi’s fault, of course. It’s right that the temples now live in a well-tended park, and glow with mellow glory in the sunlight. But would all those Romantics have written poetry and painted pictures and designed theatres and city halls that looked like temples, without Piranesi’s shrubs and shadows and melancholy gloom?

© Text © 2024 by Joe Gartman; Photographs © 2024 by Patricia Gartman. First published in Italia! Magazine, June/July 2024